Body & Health

The Women’s Health Movement

Nancy Hawley reminds us that in the early 1970s, “there were no books written by women about women’s sexual experience.”

Excerpt from “A Moment in Her Story: Stories from the Boston Women’s Movement,” a film by Catherine Russo. (Running time 2:29) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Catherine Russo Documentaries.

In 1971 Belita Cowan figured out how to use a plastic speculum, a flashlight, and a mirror to examine her own cervix — and then gave a public demonstration of how to do it yourself at a feminist bookstore in Los Angeles. This act constituted her own personal assault on the authority of the male medical profession. Soon the cause was taken up by a range of activists around the country. Women’s demand for knowledge about their bodies and greater control over their healthcare propelled the women’s health movement and permanently changed the provision of healthcare in America.

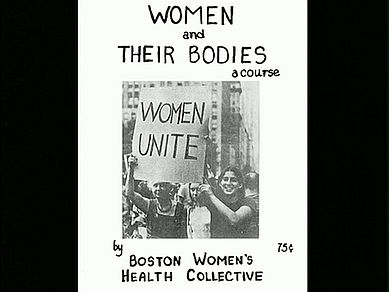

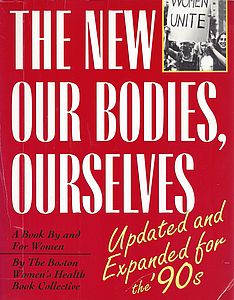

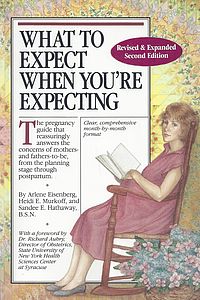

Let’s start in Boston in 1969, where a group of women who initially called themselves the “doctor’s group” began meeting to share information and trade stories about their dismal experiences at the hands of the overwhelmingly male medical establishment. Out of their research into topics such as childbirth, birth control, and venereal disease came a pamphlet called “Women and Their Bodies,” published in 1970 by a small alternative press and offered for 35 cents. To everyone’s surprise, this compilation sold 350,000 copies. In 1973 a revised and expanded version, now retitled Our Bodies, Ourselves and published by a trade publisher, became a national bestseller for the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. Today, when medical information is readily accessed on the Internet, it is hard to convey the truly revolutionary and liberating power of this handbook. Now women could be savvy consumers, not just passive and dependent clients, where their bodies were concerned.

Now let’s go to “Jane” in Chicago, an abortion referral group that helped thousands of women find safe but illegal abortions starting in 1969. When you called and left your name and number (a scary prospect, since the technology of telephone answering machines was still quite new), “Jane,” one of dozens of women who ran the service, would call you back and shepherd you through the process, including meeting you at a designated pickup spot and accompanying you to the place where the abortion would be performed. Volunteers, many of whom had had abortions themselves, cared so deeply about sparing women from life-threatening back-alley abortions that they risked arrest and incarceration, taking healthcare into their own hands. Jane shut down its referral system in 1973 after Illinois legalized abortion in the wake of Roe v. Wade.

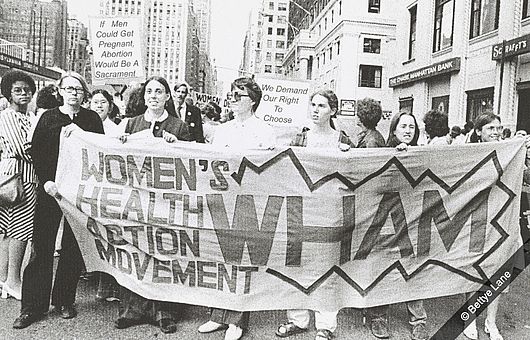

As Sandra Morgen has argued, “The struggle for safe, legal, accessible abortion was central in catalyzing women’s health activism.” Roe v. Wade acted as a spur to the founding of a number of feminist health clinics across the country. These clinics aimed to offer a broad range of reproductive and gynecological services, not just abortions, and to do so in a friendly and welcoming way that contrasted with the cold and patronizing treatment women often received in hospitals and doctor’s offices. While certain services, such as birth control, had to be provided by a licensed physician, many other aspects of feminist healthcare could be performed by trained volunteers, a good match to the self-help ethos of the movement.

Women’s health clinics were especially important in poorer communities, where their services were welcomed by women of color who saw this as an opportunity to expand medical services for their communities as well as correct past abuses. For example, many Puerto Rican women in the North and many African-American women in the South had been forced to undergo sterilization while giving birth, without informed consent, often as a condition for keeping their welfare benefits. CESA (the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse, a forerunner of CARASA, the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse), founded by Helen Rodríguez-Trías in New York City in the 1970s, brought an end to that practice, showing how activists could affect national healthcare policy. Similar efforts took place in Native American communities, such as the Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center in South Dakota, founded in 1988 and directed by Charon Asetoyer, which focused especially on fetal alcohol syndrome.

What links these stories is that they all took feminist tenets about empowerment and challenging patriarchal structures in a new direction to give women increasing control over their bodies, and especially their reproductive systems. Instead of being passive clients of a medical system dominated by men, now women challenged doctors’ carefully guarded monopoly on medical knowledge. Today, Americans function as medical consumers in a way that’s radically different from how things were in the 1960s, and the women’s health movement played a large role in this shift. Since the 1990s, the movement has been carried forward and expanded through the concept of reproductive justice based on a broad human rights perspective. The SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Health Collective represents a wide coalition of organizations that view women’s sexual and reproductive health as the cornerstone of social justice for all.

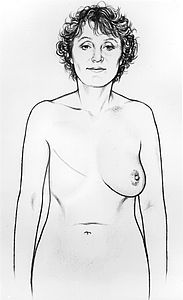

Another example of women as an organized constituency demanding better treatment from the medical establishment concerns breast cancer. In the 1970s, the standard treatment for breast cancer was a radical mastectomy, disfiguring surgery that removed not only the breast but surrounding lymph nodes and tissue. Since it was often done simultaneously with a surgical biopsy on the potentially cancerous tissue in a “one-step” procedure, a woman could literally wake up from surgery and find her breast was gone. Activists such as Rose Kushner gathered data and challenged the medical establishment to consider a less drastic response (lumpectomy, followed by radiation) in an operation separate from the biopsy so that patients could make informed decisions about their treatment. This has now become standard protocol.

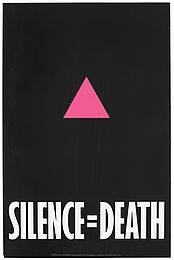

Thanks to Kushner’s activism, as well as the willingness of women such as television journalist Betty Rollin and first lady Betty Ford to go public about their bouts with breast cancer, some of the stigma of having cancer began to ease. Audre Lorde’sThe Cancer Journals (1980) explored her own experience with the disease in what became an iconic feminist text. No longer willing to stay silent, women with breast cancer eventually created one of the most effective lobbying efforts to raise funds for combating the disease, symbolized by the ubiquitous pink ribbon. Other disease communities followed suit, especially gay activists in groups like ACT UP in response to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. And they got results.

And yet the women’s health movement is not just a simple success story. With the exponential growth of the healthcare system, with or without federal healthcare guarantees, it has proven difficult for individual consumers to have much of an impact. Treatment protocols still privilege a biomedical model that marginalizes alternative medicine, holistic strategies and home childbirths. And certain issues that feminists targeted for attack have proven surprisingly resistant to fundamental change. Take hospital childbirth.

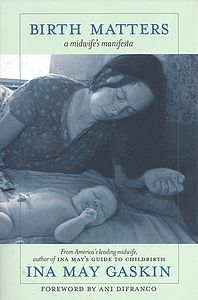

For centuries childbirth was a natural, communal process, with women coming together to guide the birth, often with the help of a trusted midwife. But in the nineteenth century, medical doctors, who were primarily male, began to set foot in this women’s world. They made childbirth more of a medical procedure, especially with the introduction of forceps to ease delivery and later the use of epidurals and anesthesia. By the twentieth century, except in rare cases, birth took place in a hospital, not at home.

Feminist health activists, some of whom were mothers or contemplating becoming mothers, challenged the status quo. Why not midwives instead of doctors? Why were women immobilized during labor? Why was breastfeeding discouraged in favor of formula? Why were so many caesarean sections being performed? After the 1960s, midwives from all backgrounds have made a steady gain in acceptance despite having been stigmatized by many in the medical profession. And there have been other changes in the modern world of birth: Family members are now allowed to be present throughout the delivery, birth coaches or doulas help with labor, hospitals set aside special birthing rooms, breastfeeding is more prevalent now that babies are allowed to remain in their mothers’ rooms, and home births are considered a viable option. Still, many physicians remain skeptical of, or inexperienced with, “normal” or “natural” childbirth. The modern process of giving birth is even more medicalized — and costly — than it was in the 1960s and 1970s. Why?

The market-driven, fee-for-service environment of American healthcare is a prime reason. New technology like fetal monitoring, and fears of medical liability, drive up costs. Seeing women’s health as a niche that could be tapped (a niche that didn’t even exist until the women’s health movement created it), hospitals and clinics offer an increasing number of services and tests, including a supposedly more personalized approach to childbirth. The dramatic increase in women doctors and healthcare professionals since the 1970s improved the diversity of the medical practice but did not fundamentally change its structure or the way doctors were trained to view childbirth; women’s healthcare is still primarily provided by physicians in hospital-linked settings where the concerns of medical insurance providers trump the opportunity for women to make the most informed choices about their birthing options. Dreams of feminists wielding their own speculums and literally taking healthcare into their own hands have not come to pass.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

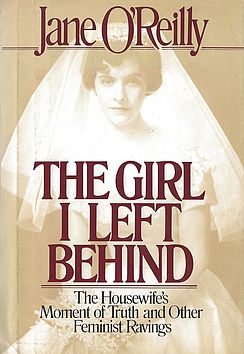

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.