Broadcasting Pioneer

That same year Thomas made his debut on radio. By 1930 he was broadcasting the first national news program to air nightly in the United States on both national networks. He started every newscast with “Good evening, everybody,” and signed off with “So long until tomorrow” — which established the practice of newscasters having a trademark opening and closing line. America was in the depths of the Depression and much of his broadcast was bad news. So Thomas decided to always end his “Nightly News” with a light-hearted or upbeat story, a convention continued to this day on all broadcast news.

Thomas was helping to establish the broadcast news format. The newscast’s steady factual style reflected his newspaper experience which was distinct from the sensational staccato of his contemporary, Walter Winchell whose background was from Broadway’s vaudeville. With clear elocution — owed to his doctoral degree in speech — and a worldly air, Thomas calmly delivered the news along with nonpartisan commentary. Thomas also set important journalistic precedents for newscasters by refusing to read advertisements or descend into the gossip columnist style of many popular radio commentators of the 1930s and ’40s.

Lowell Thomas had pioneered the use of motion pictures in reporting news with his multimedia shows on the First World War. Working with a new form of journalism — movie newsreels — was, therefore, a natural step for him. In the early 1930s Thomas was, as he regularly worded it, “flashing” to movie-goers “the news of the day” for the American Newsreel Company and then for Fox Movietone News into the 1940s. Thomas appeared in, narrated, wrote and produced these twice weekly illustrated news summaries, which were rushed to theaters coast to coast. Then in 1939, he launched the first televised nightly news broadcast — a live simulcast of his radio program. But the new medium required Thomas be in the New York studio nightly.

Audio

Clip 3

From Berlin, Thomas recalls the first television news.

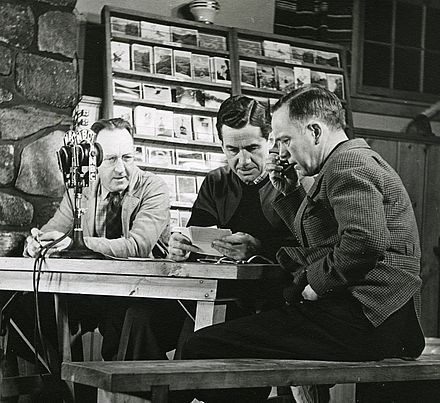

Lowell Thomas often worked out of his Pawling, New York, estate, which featured a 12-room radio broadcasting and editing facility, as well as a gymnasium, lake, golf course and ski hill. Always an adventurer at heart, Thomas was never comfortable being tied to a radio, movie or television studio — even one in his own home. His radio broadcasts were often done live from remote locations that he would use as a backdrop for his broadcast, such as Sun Valley, Idaho, or Stowe, Vermont, where Lowell traveled to pursue his active lifestyle.

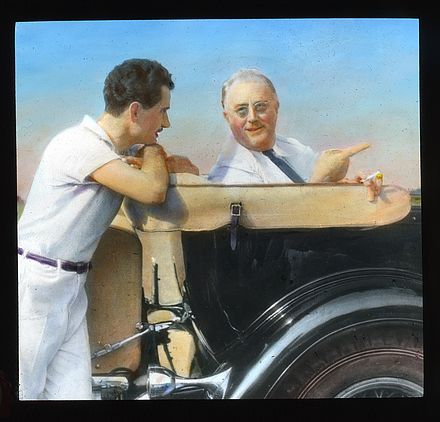

When America entered World War II, Lowell Thomas, now the president of the National Press Club and a founding member of the Overseas Press Club, was refused a passport and military press credentials by special decree of the president the United States. It was not that he was not trusted; Thomas was probably the most trusted journalist in the country. It was not that he was not qualified; he may have been the country’s most intrepid and widely traveled journalist or citizen. President Franklin Roosevelt simply felt that this man and his calm, steady broadcasts were too important to the nation’s morale to allow him to venture into harm’s way. Thomas ached to go and report, but was held back until February of 1945 when the outcome of the war was no longer in question.

When allowed, Thomas lost no time getting to Europe to join lead elements slicing into Germany. He flew over the city of Berlin, describing the German capital in flames. Connecting with his old friend General Jimmy Doolittle (of 30 seconds over Tokyo fame), Thomas joined him to fly over the Hump from India into China to report on the Flying Tigers operating there. He went into the Pacific from carrier groups to freshly captured islands Iwo Jima and Okinawa and described the war there. He found the aircraft, such as the B-29 Stratofortress, a far cry from his first trip in a military aircraft over Palestine in 1917.