Quilts as Homespun War Memorials

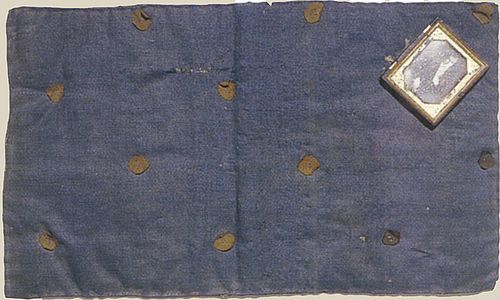

In 1855, Dr. Sylvester B. Prentiss purchased a quilt at a charity raffle in Lawrence, Kansas. It was no ordinary quilt: family lore states that the wool circles backing the ties were remnants of Revolutionary War uniforms. Boston women of the New England Emigrant Aid Society created the tied comforter to raise money to feed New England settlers in the Kansas territory. The group competed with other such charitable and political groups to campaign for the territory’s status as a free state, and the quilt demonstrated visual and tactile efforts to instill Revolutionary ideals of liberty and heritage. Prentiss later cut this unique national treasure into segments for each of his children to remember their national legacy and pass it on to their descendants even further removed from the Revolution.7

The Prentiss family Revolutionary War quilt reveals several insights about visual history, memory, and material culture. The tangible connection to a larger national cause influenced the creation and the purchase of the quilt; value lay in its material connection to the past and its effort to connect to and influence the present and future. Verifying whether or not the wool circles actually came from soldiers’ uniforms over seventy-five years old proved less important to the purchaser. Rather, the value came from its story—and the ability to pass the fabric and its memory on to future witnesses who would vote and perhaps participate in further efforts to maintain the valiant cause of the Union.8

Quilts proliferated especially during the Civil War, based on utilitarian need and traditional heritage; additionally, commemorative quilts followed during World War II as a nostalgic return to the past. Between the patchwork pieces are memories of national and regional patriotism, family stories, values, war experiences, and witnesses of sacrifice and mourning, celebration and triumph. These quilts illustrate the connection between the violence of war and the family and home front. Close examination of commemorative textiles reveals history and memory intertwined in material culture, with highly selective stories, political sentiments, and visual marks of hardship and trauma. The fabrics, patterns, colors, and stitches connect relationships, events, and causes, privileging certain war experiences and leaving out others. Although quilts cannot tell the whole story of war, they express significant war-time sentiment and capture unwritten memories. Analysis of historiography linking quilts to history and memory and careful consideration of memories of utility, family and local community, strategic designs, and provenance illustrate the memory of this textile connection between war and the home front.