Women's Community Quilts

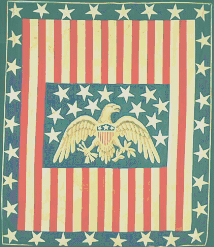

While certainly a testament to home and family, quilts also bear witness to women’s work outside the home. In the North, women mobilized publicly to assist in providing for soldiers’ needs, forming Soldiers’ Aid Societies and working under the auspices of the United States Sanitary Commission and its competitor, the Christian Commission, distributing an estimated 250,000 quilts to the front and hospitals from 1861 to 1865.32 Few of these simple utilitarian quilts exist today, probably due to their essential hardy use and non-specialized construction. The Daughters of the American Revolution boasts one in its collection; its fancy work belies little actual field use, though its strong political theme expresses publicly its Union support.

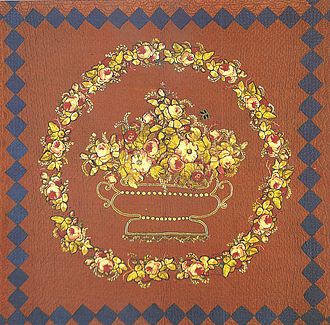

Southern women gathered to quilt, though under different social circumstances. Some formed Soldiers’ Aid Societies, though without the central organization of a Sanitary or Christian Commission. Other efforts occurred. Quilt historian Bryding Henley describes the work of Alabama women to raise money for the purchase of a gunboat for the Confederacy, with similar efforts occurring in Louisiana, South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia. The Women’s Gunboat Fund in Alabama produced quilts to be sold at a community raffle. The family story associated with Martha Hatter Bullock’s “Alabama Gunboat” quilt states that it was sold and resold several times as each purchaser returned the quilt in order to maximize profit.33 While the monetary goal to obtain a gunboat was not realized, the women’s participation in the cause bolstered their loyalty and was proudly recorded in family and community lore as wartime memory through a quilt.

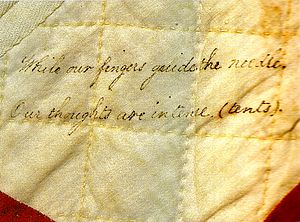

Other women gathered locally to deal with war and to commemorate what they and their loved ones experienced. Several memorial quilts illustrate this phenomenon. Friendship quilts became popular between 1840 and the outbreak of the Civil War, a period of radical change and industrialization.34 One friendship quilt, constructed by the women of Portland, Maine, demonstrates their Unionist loyalties with red, white, and blue stars and Union flag. Inscriptions penned on many blocks reveal the makers’ political and social feelings, ranging from the witty to the bloodthirsty. One in particular reads, “While our fingers guide the needles, our thoughts are intense (tents),” indicating sympathies with loved ones on the battlefront and efforts to support and sustain as well as to communicate distinct Union sentiments.35 The quilt illustrates both the community effort and overt political ideals, a memory passed down through the town’s generations.