Body & Health

Expanding Gender Identities: The LGBTQ Rainbow

How did the battle for sex education in her high school turn Shelby Knox into a powerful advocate for the LGBTQ community?

Excerpt from “The Education of Shelby Knox,” a film by Marion Lipschutz and Rose Rosenblatt. (Running time 14:17) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

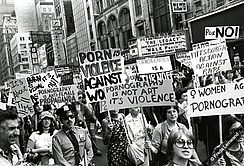

In the beginning, there was “L.” Lesbians and their gay male counterparts (“G”) were the first groups to come together under the banner of a common goal – gay liberation – starting in the late 1960s and 1970s, and were very much influenced by other social movements as well as by identity politics. The new openness about sexuality in general encouraged many lesbians and gay men to “come out” about their sexual orientation. It also brought many new recruits into the fold who had discovered their feelings for women within the supportive atmosphere of the women’s movement. “How dare you presume I am heterosexual?” challenged a provocative Women’s Liberation button. The role of lesbians in the movement caused conflict — what Betty Friedan labeled the “lavender menace” — yet because many of the problems lesbians faced were related to their status as women, the links between gay rights and feminism remained strong.

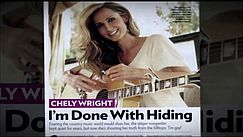

Hiding her sexuality nearly killed country singing star Chely Wright. Coming out saved her life, though she acknowledged it would diminish her wage earning.

Trailer from "Chely Wright: Wish Me Away," a film by Bobbie Birleffi and Beverly Kopf. (Running time 2:17) Used with permission. The complete film is available from First Run Features.

While the practice of women loving women has a long history, the word lesbian is a more recent invention. In the nineteenth century women often formed deep, loving relationships with other women. So prevalent and socially acceptable were these partnerships that in America they were called “Boston marriages.” Attitudes began to change when Freudian ideas became more widely accepted in the early twentieth century. With the strong Freudian emphasis on sexual expression and its privileging of heterosexuality, same-sex love (now defined by new terms such as sexual invert, third sex, homosexual, or lesbian) became more suspect and increasingly considered deviant. Women might live their lives with other women and participate in what we now identify as a lesbian community, but they didn’t necessarily publicly — or privately — identify as lesbians, often out of fear for their jobs and their respectability. They lived, as it were, in the closet. The feminist and gay rights movements brought many lesbians and gay men out of the closet and into the mainstream of American society. A prime example is the dramatic increase in popular support for gay marriage today.

So that’s “L” and “G” — what about “B”? At first bisexuality was dismissed as a cop-out for those who probably were gay but still wanted to hold on to their heterosexual privileges; today it is recognized as a valid option for those who love both men and women. Here it is helpful to think of sexuality as a continuum, with exclusive heterosexuality at one end and exclusive homosexuality at the other, with a range of expressions in between. For example, Alfred Kinsey, in his pioneering studies of male and female sexual behavior in the 1950s, employed a scale of zero to six, with three being equally heterosexual and homosexual. Instead of sexuality being a fixed or static category, increasingly it is seen as being open to multiple and fluid definitions and expressions.

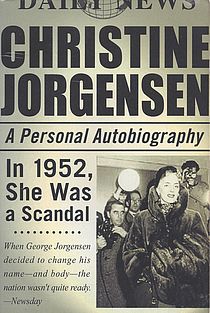

Next in the LGBTQ rainbow is “T” for trans, which can mean transsexual or transgender people, whose physical characteristics don’t match their gender identity. (Cisgender [or Cis] refers to individuals whose self-identity conforms with the gender corresponding to their biological sex assigned at birth.) How to deal with the feeling that you are trapped in the body of the wrong sex is the challenge transgender people must face. They may seek to change the physical characteristics of their sex through hormone therapy and later gender-reassignment surgery, and during this long process adopt and adjust to their cross-gender identification. The first well-known case of gender-reassignment surgery occurred in the 1950s when an American GI went to Denmark and came back home as Christine Jorgensen. A female-to-male example is the transition of Chastity Bono, the daughter of pop stars Sonny and Cher, to a transgender male named Chaz. At the tricky interface between biology and socially constructed notions of gender and sexuality, transgendered individuals have won increasing support for their decisions and actions.

That leaves “Q” for queer. This is less a specific sexual identity and more an attitude or point of view; as such, it covers a range of sexual preferences, orientations, and habits that do not conform to dominant sexual and gender norms. The derogatory use of the term queer has a long history (along with fag or faggot) for gay men. But it has been reappropriated by queer activists to establish a sense of community and assert a political identity that is proudly at odds with whatever is defined as normal. Queer theory has been enormously influential in academe, especially in cultural, literary, and historical studies, providing alternative — or queer — readings of texts as part of a broader challenge to fixed meanings for the categories of sex, gender, and sexuality.

“Q” is also for questioning. That identification includes individuals who are exploring or still making up their minds about their gender orientation. The fact that the LGBTQ label even exists confirms that the opportunities for sexual expression today are far broader and more diverse than they were just twenty or thirty years ago.

What crucial strategy did Vermont’s Freedom to Marry Task Force adopt to win broad support for marriage equality?

Excerpt from “The State of Marriage,” a film by Jeff Kaufman. (Running time 1:50) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Floating World Pictures.

In the popular mind, the sexual revolution of the 1960s is associated with a new openness about sex in popular culture, but this more recent sexual revolution, the one that is expanding sexual identities and expression far beyond normative heterosexuality, may turn out to be just as far-reaching. Feminist scholars have learned to be suspicious of categories and assumptions based on the meanings assigned to the differences between men and women (which is what gender studies is all about), but until recently, there was less inclination to question the biological differences between the sexes that underlay those gender definitions. Belief in those immutable biological differences, with the corollary that notions of masculinity and femininity follow logically from them, remains a key organizing concept for many people, what scholars call an “incorrigible proposition.” And yet a subset of humans, perhaps as many as 10 percent, have secondary sex characteristics of both sexes, making it hard to label them simply as male or female. And new categories such as transgender demonstrate that biological sex can be changed or redefined. When sex and gender are each understood as a spectrum of possibilities, sexual expression and identity turn out to be far more fluid and variable than a simple male/female binary.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.