Body & Health

Changing Sexual Attitudes and Options

Going to jail for providing contraceptives to married women? Margaret Sanger believed that birth control was the key to women’s personal freedom.

Excerpt from “Margaret Sanger: A Public Nuisance,” a film by Terese Svoboda and Steve Bull. (Running time 5:36) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

The simultaneous appearance of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the revival of feminism — both symbolized in the popular mind by the fashion trend of the miniskirt — suggested a causal link between the two, but each had its own history. The sexual revolution basically opened to women many of the pleasures and responsibilities of sexual expression that had previously been reserved for men, challenging the double standard that allowed men sexual license but punished women who claimed the same freedom. The recognition of women’s sexual needs and desires, which extended first to married women and then, somewhat more tentatively, to single women, and wider acceptance of women’s ability to choose when and with whom to have sexual relations make up some of the most far-reaching changes of recent history.

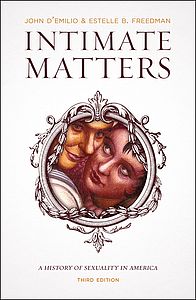

Changing attitudes about female sexuality began to take hold early in the twentieth century. The popularization of the ideas of Sigmund Freud, Havelock Ellis, and Ellen Key promoted an ideal wherein sexual satisfaction, not repression, limitation, or abstinence, was encouraged. And access to a satisfying sexual life was just as important for wives as for husbands. This view of companionate marriage was widely accepted by the 1920s. Historians Estelle Freedman and John D’Emilio summed up this change: the meaning of sexuality shifted “from a primary association with reproduction within families to a primary association with emotional intimacy and physical pleasure for individuals.”

These evolving attitudes about women’s sexuality intersected with, and indeed were made possible also by, another long-term trend: the ability to regulate conception, both to limit the number of children and to offer opportunities for sexual expression that did not result in procreation. Traditionally, without the ability to choose when to bear children and how many to have, women’s lives could be upended by an unplanned pregnancy. Although rudimentary birth control information and devices were available in the nineteenth century (which helps explain how the birthrate dropped by half from 1800 to 1900), they were generally illegal, especially after the passage of the Comstock Act of 1873. Birth control methods such as withdrawal or condoms required the cooperation of male partners, which was not always forthcoming; female methods such as douching, using pessaries (an early form of diaphragm), or limiting intercourse were better than nothing but were still hit or miss.

Margaret Sanger, a public health nurse with feminist sensibilities, set out to change women’s lack of control over their reproductive lives by opening the first birth control clinic in the country in New York City in 1916. She was quickly arrested. Thus began her forty-year campaign to make birth control legal and widely available. Her device of choice was the diaphragm, which maximized women’s control over the sex act. In the 1920s Sanger deliberately allied herself with the medical establishment in the hope that their support would bolster what was still seen as a dangerously radical cause. In effect, she gave doctors control over the dissemination of birth control information and devices. At the same time she located women’s sexuality squarely within the construct of marriage, a far less radical stance than her original focus on women’s sexual liberation.

Who should be allowed to buy contraceptives? Meet the pioneering lawyer who won the landmark Supreme Court case protecting the right to privacy.

Excerpt from "Catherine Roraback Tribute," a film by the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. (Running time 5:56) Used with permission.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Sanger successfully chipped away at restrictions limiting access to birth control for married women, although the issue wasn’t finally settled until the 1965 Supreme Court case of Griswold v. Connecticut. Far more controversial was the idea of single women having easy access to birth control, precisely because that meant condoning premeditated sexual activity outside the institution of marriage. This is where the birth control battles were fought in the 1960s and beyond.

Single women had already been expanding the boundaries of acceptable sexual expression over the course of the twentieth century, as Alfred Kinsey found in his 1953 study of female sexual behavior. But there were still clear lines about what was considered proper sexual behavior for most young women, depending on the norms of various communities. Generally speaking, extensive “petting” short of intercourse was tolerated; “proper” or “morally clean” young women were supposed to keep their virginity for their wedding night. “Going all the way” carried a distinct social stigma, as well as the risk of unplanned pregnancy.

If single women did engage in sexual relations (as many clearly did), they often did so without access to reliable birth control information. One mistake could literally change a woman’s life. If a teenager or young adult found herself pregnant, she could either hastily marry the father, seek an illegal abortion, raise the baby as a single mother, or put the baby up for adoption.

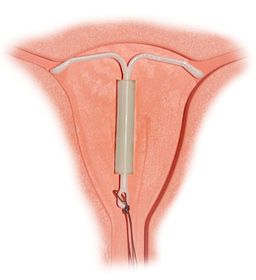

The possibilities for increased sexual activity without fear of pregnancy took a giant leap forward in the 1960s with the introduction of two new forms of contraception, the birth control pill (first offered in 1960 and widely available by mid-decade) and the intrauterine device (IUD). Somewhat ironically, wider access to safe, reliable contraception put more pressure on women to engage in sexual relationships with men now that fear of pregnancy was removed. And yet feminist consciousness raising helped women imagine sexuality from a female point of view, not just in terms of pleasing men. This was a truly revolutionary perspective for many women.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

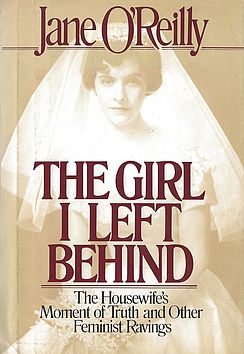

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.