Politics & Social Movements

Discord Among Women

Who speaks for American women? Two conferences held in Houston, Texas in 1977 offered strikingly different answers to this question.

Excerpt from “Sisters of ’77,” a film by Cynthia Salzman Mondell and Allen Mondell. (Running time 11:23) Used with permission. The complete film and discussion guide are available from Media Projects Inc.

Not all women jumped on the feminist bandwagon in the 1970s. While support for the women’s movement grew dramatically (in a 1975 Harris poll, 63% of women said that they favored “efforts to strengthen and change women’s status in society”), there were still significant segments of the population, female and male, who expressed either concern about the rapidity of social change or outright disapproval of feminism’s goals and priorities. The general rightward political turn, symbolized by the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan, encouraged the revival of conservativism.

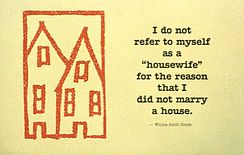

One of the strongest flashpoints in the discord caused by feminism was women’s traditional role as mothers and housewives. Women who chose to stay home with their children felt that their choices were being denigrated by the feminist focus on finding fulfillment in work and professions outside the home. Even though feminists emphasized that women should be allowed to choose their life options, including traditional domestic roles, the women’s movement was often portrayed as hostile to homemakers.

In the 1970s, conservative women began to speak out publicly and mobilize in support of traditional gender values, especially their core belief that there were profound and immutable differences between the sexes. While much of this initial mobilization occurred on the local level, especially in evangelical churches, Phyllis Schlafly quickly emerged as the main spokesperson for the cause in the mainstream media.

Schlafly offers a glimpse of the changing priorities of conservatism within the Republican Party. A lawyer, an unsuccessful candidate for Congress, and the mother of six children, she became well known in Republican circles when she co-authored a book about Barry Goldwater, A Choice, Not an Echo, that figured prominently in his unsuccessful 1964 presidential campaign. Schlafly and other conservative Republicans were then mostly concerned with promoting a vehement Cold War anti-Communism and encouraging fiscal responsibility.

What confronted Michigan feminists while they were working for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment?

Excerpt from “Passing the Torch,” by Carol King. (Running time 4:50) Used with permission. The complete film is available from King Rose Archives. For more information, visit Veteran Feminists of America.

In 1972, however, Schlafly took up the cause of anti-feminism. “The claim that American women are downtrodden and unfairly treated is the fraud of the century,” she argued. “The truth is that American women never had it so good. Why should we lower ourselves to ‘equal rights’ when we already have the status of special privilege?” A charismatic speaker and superb grassroots organizer, Schlafly successfully wove together homilies about women’s traditional feminine roles (even though, as her critics pointed out, she hardly lived such a life herself) with a concrete political agenda. In 1972 she founded STOP (Stop Taking Our Privileges) ERA, which in 1975 became the Eagle Forum.

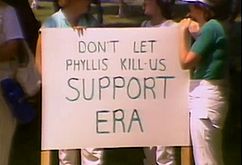

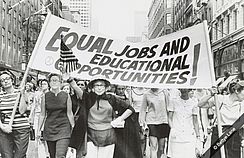

During the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston, Schlafly and her Eagle Forum showed that right-wing women could organize and influence politics just as effectively as progressive feminists. Following up on the designation by the United Nations of 1975 as International Women’s Year (later expanded into the International Decade of Women), Congresswomen Bella Abzug and Patsy Mink convinced Congress to authorize $5 million for a conference of American women, with delegates to be selected at conventions in each of the fifty states. Feminists dominated the selection process in most states, and close to twenty thousand women gathered in Houston as delegates and observers. After four days of intense discussion and politicking, the assembled women agreed unanimously on a national plan of action, which included twenty-six resolutions on topics such as violence against women, the special problems of “minority” women, lesbian rights, and reproductive freedom, including the right to abortion.

Across town, almost fifteen thousand conservative women, assembled by Schlafly and other right-wing leaders, held their own conference. Instead of planks supporting abortion rights and the ERA, delegates vowed to uphold traditional pro-family values, especially the right to life, the new catchword of the anti-abortion movement. The competing Houston conferences, both professing to represent the interests and values of American women, demonstrated that the category of “woman” was too broad politically and culturally to be represented by a common set of values. And Schlafly’s message that women had something to lose, not something to gain, from feminism continued to resonate in the increasingly conservative political climate. Nowhere was this clearer than in the battle over the ERA, the issue most associated in the public mind with feminism in the 1970s.

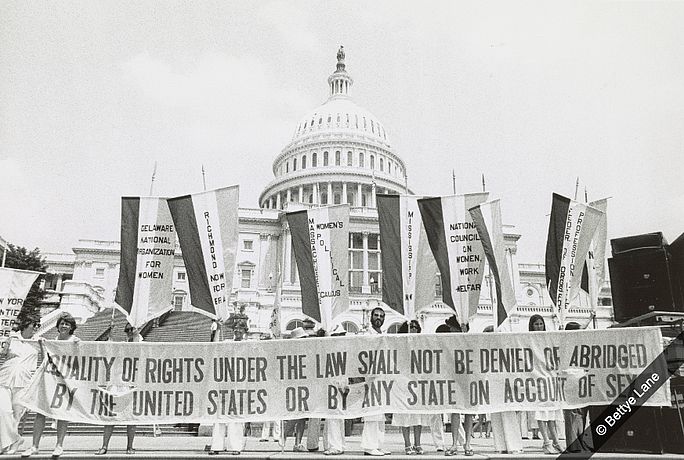

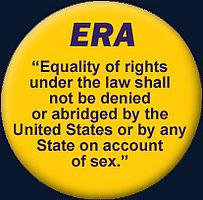

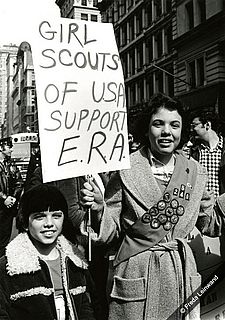

For all the controversy over its meaning, the language of the Equal Rights Amendment is straightforward: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on the basis of sex.” The proposed constitutional amendment was first introduced in 1923 by Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party as the next logical step after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the vote. But instead of providing a unifying cause to keep the organized momentum of the suffrage movement going forward, the ERA proved to be an incredibly divisive issue among activist women, first in the post-suffrage years and then (for entirely different reasons) in the 1970s.

Why would women, including many social reformers, be opposed to equal rights under the law? In the 1920s the main stumbling block was protective legislation. Such laws — which limited the number of hours that women could work, banned women’s work at night, or prescribed a minimum wage — offered women workers benefits and rights that courts were unwilling to extend to male workers at the time. Advocates of protective labor legislation saw laws for women as a wedge to more extensive legislation that would make the workplace more just for all workers. Opponents of this legislation argued that laws based on the supposed physical weakness and emotional frailty of working women were patronizing and outdated; they advocated for the ERA. Since the proposed ERA would likely have made protective legislation illegal, many women we would now consider feminists opposed the amendment, sometimes adamantly, as late as the 1960s.

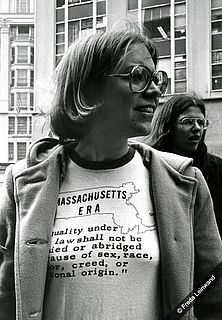

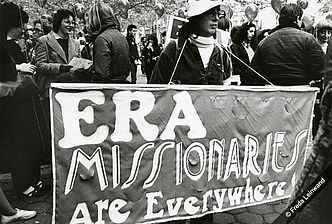

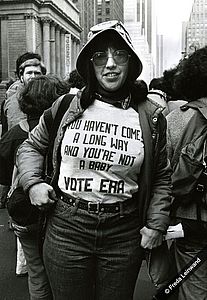

As the women’s movement picked up momentum, politicians and activists began to look at the ERA with fresh interest. After years of Congressional inaction, both houses of Congress passed the amendment in 1972 and sent it to the states for what seemed likely to be swift adoption. In the first two years, thirty-four (out of a necessary thirty-eight) states quickly ratified the amendment, jockeying to go on record in favor of women’s equality. But by 1974–1975 the momentum had slowed; Indiana was the last state to ratify it, in 1977. Activists won a three-year ratification extension, to 1982, but considerable lobbying in Florida, North Carolina, and Illinois failed to sway the conservative legislatures in those states, and the ERA went down to defeat. While various states have passed their own equal rights amendments, efforts to revive the federal amendment have come to naught.

What had happened? The battle over the ERA drew support and energy on both sides. The National Organization for Women made passage of the Equal Rights Amendment its highest priority, and devoted much of its institutional and financial resources throughout the 1970s and early 1980s to achieving that goal. The ERA was endorsed by a wide range of women’s and labor organizations, including the American Association of University Women, the League of Women Voters, and the AFL-CIO, and public opinion polls showed strong popular support for its adoption. But as has been true in other campaigns for constitutional amendments, once the ERA became controversial, it was very difficult to reverse the course. Add to that the challenge of mounting separate ratification campaigns in a variety of states in an increasingly conservative political climate, and suddenly what had seemed like a done deal was very much in doubt.

The ratification drive also faced a highly organized, politically sophisticated opposition, led primarily by Phyllis Schlafly. Mobilizing masses of grassroots women from a base in evangelical churches and right-wing political groups, ERA opponents descended on state capitals, dressed in their Sunday best and often bearing home-baked bread and apple pies, symbols of their traditional domestic roles. Their message: We like being treated as women, we don’t want to be treated like men. Traditional homemakers feared that alimony and child support might be abolished, and that stay-at-home mothers would be forced into the workforce. And there were also frivolous assertions, such as the argument that the ERA would prohibit separate toilets for men and women (the “potty” issue). Supporters of the amendment argued that none of these were likely outcomes, but those supporters made little headway in countering the conservative attacks.

The Equal Rights Amendment also got tangled up in some of the hot-button issues of the day. The first was abortion, which became a contentious national issue in January 1973 when, just as the state ratification drives for ERA were getting under way, the Supreme Court issued the Roe v. Wade decision. While supporters argued that the ERA would not mandate abortion or public funding for it, opponents convincingly played on fears that there was a link between the two.

Just as divisive was the question of whether the ERA would cause women to be drafted, a sensitive and serious issue while the Vietnam War was winding down. Many feminists tried to avoid the question by supporting the scheduled end to the draft in June 1973, but Americans in the 1970s were still anxious about the specter of their daughters fighting and dying in foreign wars. In the years since, women have entered practically every aspect of the military, including combat, without outcry and indeed with strong public support.

After the ERA was defeated in 1982, feminists debated whether it had been a good decision to focus so much organizational effort on a single issue. On the positive side, having a clearly defined goal that a broad range of women and men could mobilize around allowed for a concentrated campaign that targeted political leaders at the same time it mobilized popular grassroots support for the idea of gender equality. Also appealing was the chance finally to bring to fruition a campaign for equal rights that had begun right after suffrage. And yet the campaigns for state ratification (and in some cases, campaigns to keep states from rescinding their earlier ratification once the political climate had changed) were enormously time-consuming and costly, in terms of money and energy. Sure, equal rights were important, but so too were a range of other items on the feminist agenda, such as reproductive rights, affordable childcare, equal pay, and opposition to sexual harassment. There were also lingering doubts about how much impact the amendment would actually have — beyond, of course, its enormous symbolic value.

In the end, the failed campaign to add a formal endorsement of equal rights for women to the U.S. Constitution proved how difficult it was to win a consensus for an amendment once it became a lightning rod for a host of other issues (especially abortion) in the increasingly polarized political climate of the 1970s and 1980s, and created a telling reminder of the diversity of opinion regarding women’s roles.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

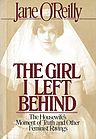

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.