Workplace & Family

Women in the Military

“I’m Hispanic. I’m female. I’m short.” Alfie Alvarado Ramos challenged long-standing prejudices to achieve her dream: a successful military career. Ramos is now: Director, Washington State Department of Veterans Affairs.

Excerpt from “Service: When Women Come Marching Home,” a film by Marcia Rock and Patricia Lee Stotter. (Running time 7:52) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Service The Film.

Back in the 1970s, the idea of women being drafted was so unimaginable that it helped to kill the Equal Rights Amendment. Now women serve and die in the armed forces alongside men. The story of women in the military is history in the making. Indeed, their experiences serve as a microcosm of many workplace and family issues.

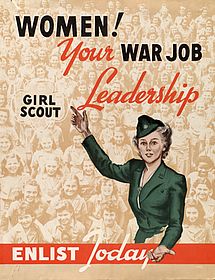

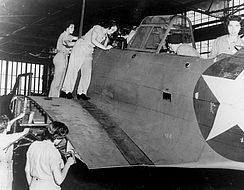

It is hard to imagine an institution more “male” than the military, yet women have volunteered and served throughout the twentieth century. For example, during World War II more than 350,000 women served in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) or the U.S. Naval Reserve (Women’s Reserve), nicknamed WAVES. From the 1940s on, most military personnel needs were filled via the draft, which applied to American men over the age of eighteen. In 1969, as the Vietnam War wound down, the military instituted a draft lottery, and in 1973 conscription ended. President Jimmy Carter proposed reinstituting draft registration in 1980, and there was talk of registering women as well, but this idea was shot down by the Supreme Court in Rostker v. Goldberg in 1981.

At this point the United States committed to an all-volunteer army, and women were suddenly a much bigger part of the picture. Post-Vietnam, armed services morale was quite low. One way to fill the quotas was to recruit and train more women, although most of the military was hardly eager to have them in anything but support roles. “Maybe you could find one woman in ten thousand who could lead in combat,” General William Westmoreland predicted, “but she would be a freak and we’re not running the military academy for freaks.” He was not exactly putting out the welcome mat.

Yet by the time of the first Gulf War in 1990–1991, more than 40,000 women were deployed in Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield. In retrospect, the Gulf War became a turning point in popular acceptance of women’s expanded role in the military. Twelve women lost their lives during the conflict. Americans began recognizing that military women were making significant contributions and sacrifices for their country.

During Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, women made up approximately 14 percent of the armed forces. The American public was riveted by the story of Private Jessica Lynch, who was captured and later released to great fanfare, but the fate of her best friend, Lori Piestewa, received much less attention. Piestewa, who was driving the Humvee transporting Private Lynch, was fatally wounded in the attack and became the first woman to die in that conflict.

The daughter of a Hopi father and a Hispanic mother, Lori Piestewa represents the diverse racial and ethnic makeup of the modern army: 47 percent of women are non-white. In 2011, African-American women made up 31 percent of enlistments, twice their representation in the general population; in contrast, African-American men’s enlistment rate of 16 percent matched their civilian numbers. As had been traditionally true for working-class men, many women now join the military, just as Piestewa and Lynch did, to earn good pay and learn technical skills while serving their country. College tuition, healthcare, and high-quality childcare are other tangible benefits that make the military an attractive option for many young women.

It was not always this way. The armed forces put up roadblocks for women’s advancement at practically every step along the path. When women started joining the all-volunteer army, there were still strong vestiges of male supremacy everywhere, such as prohibitions against women serving on any ship at sea or training as pilots. Service academies such as Annapolis and West Point began admitting women only in 1976, and then only with extreme reluctance after legal challenges. The graduates of these institutions are the designated future leaders of the armed forces, but female graduates faced enormous challenges. The rule that proved the greatest barrier was the one excluding women from “combat-related” job categories, which in 1980 kept them out of a whopping 73 percent of all jobs. Even though more categories gradually opened over time, the combat exclusion meant that it was very difficult to get the experience and training necessary for promotion.

The lines between combat and non-combat became especially porous during the Iraq and Afghanistan operations, where there were no front lines, just the constant threat of engagement. Given the numerous land mines and booby traps, few jobs were more dangerous than driving a truck (remember Lori Piestewa), but that was classified as a non-combat position. Not until 2012 was the combat exemption finally lifted.

As more evidence accumulated that women were as capable as men in modern military warfare, why was the military still so resistant to admitting that women soldiers were the equals of men? The deeply ingrained misogyny of traditional military service proved extremely hard to overcome. Many men seemed especially threatened by women’s success. “Look, I can handle anything,” one male test pilot told a female recruit, “but I can’t handle being worse than you.”

When will it end? At least 20% of female veterans have been sexually assaulted while serving.

Excerpt from “The Invisible War,” a film by Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering. (Running time 7:53) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Not Invisible.

The way that women in military service were devalued made some of them targets for sexual harassment and assault. A shockingly high proportion of women reported being sexually assaulted, including being raped, while in the service. And these sexual assaults did not come from enemy combatants: As a Congressional panel was told in 2004, “Women serving in the U.S. military today are more likely to be raped by a fellow soldier than killed by enemy fire in Iraq.” If a woman decided to report the assault to her commanding officers, she often found her superiors far more concerned with protecting the military career of the male perpetrator than with bringing justice to the victim. In 2013, Senator Gillibrand introduced the Military Justice Improvement Act to require independent courts-martial for certain crimes, but the bill has remained in committee. However, the U.S. Army has established new procedures for reporting crimes that bypass the chain of command.

Military women who were lesbians faced special challenges. Even though many lesbians and gay men have proudly served in the armed forces, their sexual orientation could be official cause for being discharged. In the 1990s, the Clinton administration instituted a “don’t ask/don’t tell” policy, which forced gay soldiers to keep quiet about their sexual orientation as the price of continued service. In 2007, a Pentagon study showed that a much higher proportion of the people discharged for being openly gay were women: 46 percent in the Army, even though women made up only 14 percent of the personnel, and 49 percent in the Air Force, compared with their 20 percent representation. The recent lifting of the “don’t ask/don’t tell” policy may make life easier for lesbians in the armed forces, but they still face lingering homophobia and a host of challenges not faced by straight soldiers.

One area that might actually be better for women in the military than civilians is access to daycare, thanks to the Military Child Care Act of 1989. When the army moved toward volunteer status, it realized that its recruits, male and female, were likely to be older and stay in the service longer than draftees, meaning they were more likely to be married and have small children. So the Department of Defense instituted a policy of high-grade daycare that would be the envy of many civilian parents, featuring well-run childcare centers that offered good pay (far above the minimum wage that is the norm in civilian life), full benefits, and training for staff, which cut down dramatically on turnover. As a result, 98 percent of the military childcare centers are nationally accredited, versus 8 percent in civilian life. Of course this extensive system mainly applies stateside, not for deployments. Married and single women in the military with children all juggle the demands of work (in this case, being deployed out of the country, often for as much as a year) with family life. The emotional anxiety of leaving children for months at a time is one of the main reasons women leave the military.

The story of women in the military is therefore both celebratory and cautionary. Since the 1940s women have shown that they were capable and committed members of the armed forces, willing to serve and risk their lives alongside men. Old fears that they would be afraid in combat, too frail to carry heavy equipment, or unable to perform duties while menstruating or during pregnancy have been shown to be false. And yet there is still a palpable resentment among many hardcore military men who feel that the only place for women is in support roles, or that women are getting a softer deal. And that disdain fuels a culture of sexual assault and violence that is rampant in military life. Sergeant Jennifer Hogg put it well: “Women in the military are regarded as second-class citizens, ripe for abuse.” As with so much else in our broader story, there is still plenty more to be done before women are fully integrated into the modern military. But don’t lose sight of how far they have come in infiltrating one of the last bastions of masculine privilege left in contemporary American life. If a woman can make it in the military, she probably can make it anywhere.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

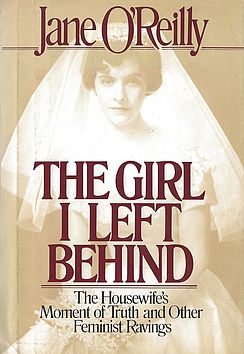

1971 The Click! Moment

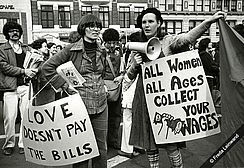

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.