Figure 6: Washington Crossing the Delaware

Works such as “Washington Crossing the Delaware” were reproduced with such frequency in pictorial works such as Spencer’s History of the United States that they came to seem synonymous in the popular mind with the events they described. [Image 52] Viewers felt they were “in the presence of veritable ‘snap-shots’ of historical events” when they saw images such as Leutze’s much-circulated and clichéd depiction, its imagery crowding out all other competing conceptions of the event, either visual or literary. [81] Leutze’s Delaware River episode is treated pictorially “more dramatically than facts warranted,” one critic noted, the painter having positioned Washington at the vanguard of the procession like a “modern Moses” despite numerous historical accounts testifying to the general’s location near the rear of the formation. [82]

But most Americans, as anxious to have agreement in their art criticism as they were in their political life, saw in Leutze’s overstated hero a hopeful and believable model for deliverance from discord. If Leutze’s illustration did not convey with accuracy what happened during Washington’s crossing, it depicted what many Americans believed could have (and ultimately should have) happened. Unwilling or unable to challenge or refute such compelling imagery as Leutze’s, Spencer adjusted his literary description of Washington’s crossing to suit the painter’s symbolic pictorial language. “The night proved to be most intensely cold; the Delaware was choked with masses of floating ice; the current was strong; and the wind blew keenly and sharply,” Spencer wrote in the History of the United States, adding that the “soldiers, exhorted to be firm, remembered, with unconquerable indignation, the outrage and injury inflicted upon the people of New Jersey by the insolent enemy, and the no less insolent and vindictive Tories. They were now ready to do or die for their houses and their country.” [83]

Mark Twain [Image 53] spoofed characteristically on the ubiquitous appearance of Leutze’s imagery above mantels and in “thunder-and-lightening crewels” on the walls of frontier households, commenting in Life on the Mississippi that Leutze had created a “work of art which would have made Washington hesitate about crossing, if he could have foreseen what advantage was going to be taken of it.” [Image 54] Such an injudicious repetition of an image, Twain implied, was unhealthy for a nation already given over to slavish mimicry in its visual representations. [84]

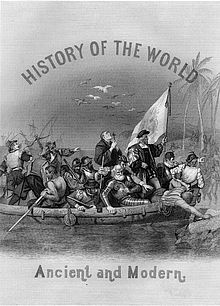

Despite Twain’s warnings, artists like Chappel experimented endlessly with the Leutze formula, even adapting its embarkation format for imitative illustrations that had nothing to do with George Washington. Chappel’s frontispiece for Spencer’s History of the World, for instance, retained the compositional structure of the Leutze original but inverted the form and transposed the historical context by substituting Columbus for Washington [Image 55]. Twenty years after Leutze’s original painting had been exhibited in the United States, its features had become so standardized as to have encouraged Chappel to imagine Columbus as a conquering patriot and the Native Americans of the Caribbean as would-be Hessian and British resisters.