Family and Utilitarian Quilts

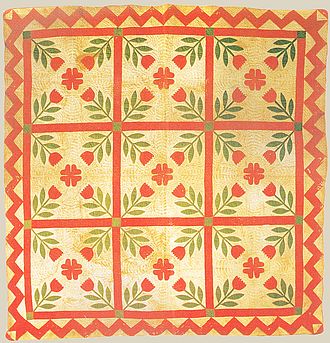

Quilts provide a view of distinct female war efforts. According to quilt historian Barbara Brackman, women had little to offer during the Civil War but their sons and husbands and their domestic skills as they maintained the home front. “Needlework, chief among their skills, became the war work that most occupied women in the Union and the Confederacy.”21 Women sent quilts with their loved ones to warm them and to remind them of home. These quilts, according to quilt historian Catherine A. Cerny, extended the physicality of the family.22 For example, Elizabeth Skiles Ward packed her wedding quilt, an intricate tulip appliqué, for her husband, Major Lemuel Ward of Garysburg, North Carolina. The Confederate officer spread the quilt on the ground each night, when his thoughts must have returned home as the quilt reminded him of a faithful wife.23 Quilt historian Lynn A. Bonfield writes about letters from Vermont soldiers requesting quilts. Hazen B. Hooker wrote to his parents, “Perhaps you could send one that has shielded me from the cold in days past.” His request was not only for warmth, but for familiarity. Bonfield realizes that “the memories a quilt evoked comforted the boys as much as did the warmth from the extra layers a quilt provided.”24 Quilts, then, commemorated home while on the front lines, then remembered war as the fabric remnants and their stories passed on to future generations.

Sometimes the quilt’s primary utilitarian purpose memorializes war beyond the warmth and cover necessary at the battlefield. Commemorative value appears in recounting its utility. One family quilt commemorates the Civil War in an especially poignant manner, without flags, battles, or symbols. A summer log cabin quilt was sent with young soldier James P. Hargrove to the front line, who died in battle in Knoxville, Tennessee. A family slave retrieved Hargrove’s body, immediately recognizing him wrapped in the quilt made by his mother. He brought the body home for burial.25 The quilt, with its story, ragged and torn, survived for later generations as a mark of grief and pride in contributing to the Confederate cause. According to quilt historian Gail Andrews Trechsel, quilts often serve as tangible modes of mourning and remembering. As a temporary or final covering for the body, the quilt acts as a shroud or coffin. In this case, the quilt then becomes a physical connection to or memory of the dead, potentially acting as both healing force and memorial.26

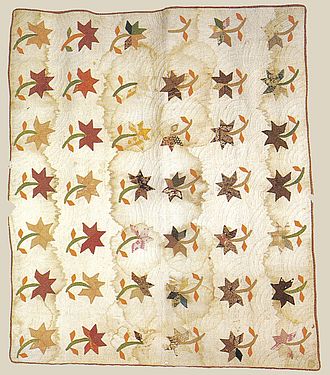

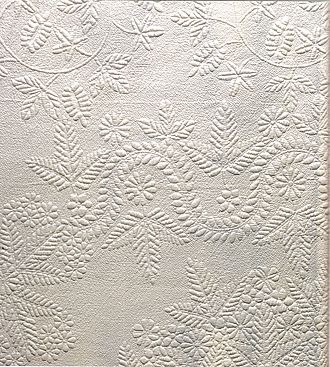

Quilts also serve as memorials of hardship. Serving in very utilitarian ways to warm and cover soldiers, quilts often came to bear the marks of their service. These marks, then, became their own war memorials, like the remains of bullet holes from the Civil War in the Tennessee state capitol. The Baugh family’s Lone Star quilt, for example, still shows the bloodstain of soldier James Elem Baugh from his wounds at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864.27 When the Pope family heard a battle was coming to their area in northwest Arkansas in March 1862, they buried valuables in a quilt to save them from Union soldiers. Many family members died in the Battle of Pea Ridge, and the quilt continues to bear stains from its buried battle scars. While the spots probably could have been easily cleaned, their remnant testifies to the hardship of that war moment.28

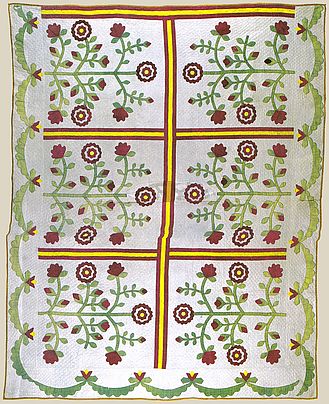

Other quilts prove value in stories of assistance to soldiers. A beautiful Rose Tree quilt, marred by a carefully-patched hole in its center as a testament to war deprivation. The story goes that a Southern soldier traveling home on foot, suffering from cold, stole the quilt as it hung over a clothesline outside a Virginia home. After cutting the hole to fit the quilt as a poncho, he made his way to Knoxville, Tennessee, where exhausted and penniless, he was charged with public vagrancy. Constable John R. Nelson, a Confederate sympathizer, pitied the young soldier and offered to buy the quilt, thus providing the soldier with money and saving him from time in the local jail. While the hole has been carefully repaired, its trace is still visible, and its story memorializes efforts to participate in the war.29

An appliquéd Irish Chain quilt carries with it the story of its benefactor. John George Bauer, a soldier in the 5th Iowa Union Cavalry, was wounded in northwest Tennessee. Insisting that his arm not be amputated, Bauer remained in the area to recuperate. With the assistance of a kind local woman, Mary Benson Lockridge, he recovered sufficiently to return to his unit. Lockridge draped her Irish Chain quilt over the soldier’s shoulders to hide his Union blue uniform, enabling him to slip past Confederate guards to safety. The quilt remained in his family as a textile testament of kindness rarely experienced in harsh war.30

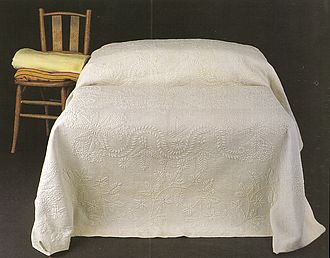

Barbara Broyles of Rhea County, Tennessee, loaned several quilts to Confederate soldiers stationed nearby. Unfortunately, when soldiers returned one white cotton stuffed work quilt, they returned it covered in typhus germs, and both Barbara and her husband died within four days. The quilt survived, and the family continues to tell the story of the sacrifice of their parents due to their Confederate compassion.31 These quilts bear heroic stories, often mythic in nature. Authenticity may remain questionable—would a family really want to preserve such germs? However, for these families, their stories prove more valuable than the truth, commemorating values of hardship and participation. Holes, stains, wounds, disease—the absence of color and fabric—witness war and its memory in stark visual and tangible ways.