Click! in the Classroom

The Jeannette Rankin Brigade, 1968:

Women’s Peace Activism

Grade Level: Grades 10-12 | Estimated Time: One class period |

Introduction

This lesson plan introduces students to the Jeannette Rankin Brigade and provides an example of how women came together in the late 1960s to influence politics and foreign policy. It is also an example of differences among women, especially differences of generational approaches to politics in this era.

On January 15, 1968, about 5,000 women from across the nation came to Washington, D.C. to protest the war in Vietnam. They called themselves the “Jeannette Rankin Brigade” in honor Jeannette Rankin, a suffragist who became the first woman member of the U.S. Congress and only member who voted against both world wars. The protest was organized by Women Strike for Peace (WSP), whose members included co-founder Dagmar Wilson, civil rights activist Ella Baker, and Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King, Jr. WSP had gained national attention in the early 1960s when it rallied women around the slogan “End the Arms Race, Not the Human Race.” Historians agree that WSP played a crucial role in the passage of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, signed by the U.S., U.S.S.R, and United Kingdom in 1963.

Joining WSP for the protest in Washington were members of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which was founded in 1915 as the Woman’s Peace Party. Also participating were members of the New York Radical Women (NYRW), a new women’s liberation group. Historian Amy Swerdlow writes that the “fact that Jeannette Rankin was a suffragist, remembered for her feminist pacifist stand, attracted a group of young women who decided to use the event to insert feminist consciousness and demands into the struggle for peace.”

However, the NYRW thought the Brigade’s approach to protest, which including petitioning Congress, and its “ladylike” demeanor were more harmful than helpful. At a meeting that followed the march to Congress, NYRW led a “Burial of Traditional Womanhood” at Arlington National Cemetery. In their invitation to the burial, the NYRW called on women “to sacrifice your traditional female roles. . . . Until we have unified into a force to be reckoned with, we will be patronized and ridiculed into total political effectiveness.”

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to demonstrate an understanding of women’s advocacy of peace and disarmament.

Students will be able to connect the feminist movement to other movements for social justice and equal rights.

Essential Questions

How have people confronted governments to enhance human rights?

How do movements for political and social change gain momentum?

Materials

Technology Needs: Computer with Speakers and Internet Access

This Lesson Plan (PDF)

KWL Chart (PDF)

Firestone, “The Jeannette Rankin Brigade: Woman Power?” Notes from the First Year (June 1968): 18–19 (PDF)

Amatniek, “Funeral Oration for the Burial of Traditional Womanhood” (PDF)

Warren Hinckle and Marianne Hinckle, “Women Power.” Ramparts Magazine (February 1968): 22-31 (PDF)

Warm Up Activity: Word Association and Discussion

Divide the class into small groups or pairs.

Write on the board “Sisterhood is Powerful.”

Have the students discuss this term with each other.

Guide them by suggesting they define “sisterhood” and “power.” They can then attempt to find examples of how the terms fit together.

Bring the class back together and have them share their findings.

Tell the class that they will be looking at feminist peace activism in the 1960s to understand how two generations of women worked together, (sometimes uneasily), for peace.

Main Activity: Jigsaw on Jeannette Rankin Brigade

Divide the students into 4-person jigsaw groups.

Have the groups go to Click.

Guide them to the chapter on Politics and Social Movements. Tell them to look at the timeline on the left side of the page.

Have them find the entries for “1941 Jeannette Rankin” and “1968 Jeannette Rankin Brigade.” Each entry has links to the sources they need:

1941: They should click on the link to “Biography, U.S. Congress.”

1968: They should click on the link to “The Jeanette Rankin Brigade” by Shulamith Firestone. (Note: Firestone spells Jeannette as Jeanette.)

Have all the students read the biography and the Firestone essay.

Students should also have the option of reading “Funeral Oration for the Burial of Traditional Womanhood” by Kathie Amatniek.

Assign each student in the group to one segment of the Firestone essay. The segments are:

Formation and Traditional Protest [Paragraphs 1 & 2]

Alternative Protest [Paragraphs 3 & 4 (including slogans)]

Invitation [Paragraph 5 & “The message” in italics]

Lesson Learned [Paragraph 6 to the end]

Have one student from each jigsaw group join other students assigned to the same segment in an expert group.

Have the expert group discuss what they have learned from their reading.

Give the students time to discuss the main points of their segment and prepare the information they will share with their jigsaw group.

Have the students return to their jigsaw groups.

Have each student present their segment to the group.

Other students in the group should ask questions for clarification.

Complete the jigsaw exercise by having students fill in a KWL Chart (PDF).

Students may ask about the Ramparts article mentioned in the second to the last paragraph. A link to this article is in the Materials section of this lesson plan.

Discuss other research opportunities about this historic moment, generational conflicts and cooperation, the development of feminist activism, the Vietnam War, and the Cold War.

Extension Activity: Document Analysis

Hand out a Document Analysis Worksheet (PDF) to each student.

Hand out Amatniek’s “Funeral Oration for the Burial of Traditional Womanhood” (PDF).

If there is time, ask for volunteers to read sections of the oration.

Have the students complete their worksheets after the presentation.

Begin a discussion about the oration by having students:

Provide a summary of the oration.

Place the oration in its historical context.

Identify key words used by the author.

Continue the discussion by asking students how the author defines “traditional woman” as a “problem.”

Conclude with a discussion by focusing on why the author defines “traditional woman” as a “problem.”

Common Core Anchor Standards

Writing

Research to Build and Present Knowledge:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.7

Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

Speaking and Listening

Comprehension and Collaboration:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

Presentation of Knowledge and Ideas:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.4

Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

Next Up: Lesson Plans for Body & Health

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

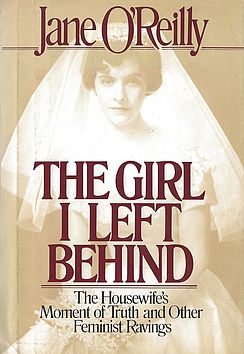

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.