Lawrence and The Show

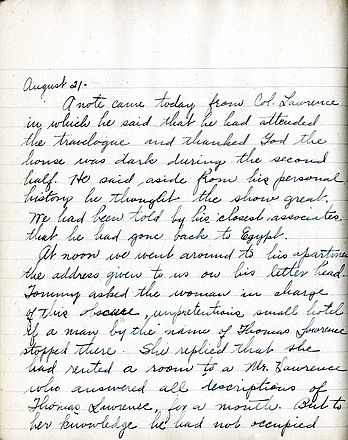

When Thomas opened the Show in London, Lawrence was in seclusion, depressed over his failure to gain any concessions for the Arabs from the colonial powers at the Paris Peace Conference. It is hard to fully convey the publicity and success that Thomas’ production enjoyed. Certainly it was impossible for Lawrence to ignore, and on the August 21, within the first week of the Show’s opening, Thomas received a note from him.

“Dear LT: I saw your show last night and thank god the lights were out! —TEL”

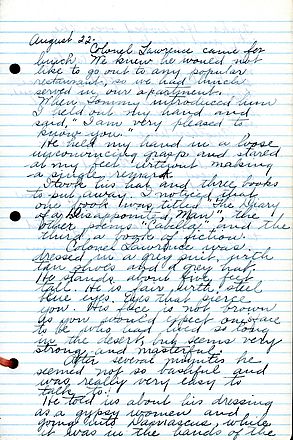

The next day Fran Thomas recorded meeting Lawrence for the first time over lunch and according to Mrs. Thomas, Lawrence was a frequent visitor throughout the fall of 1919 to the Thomas’ London flat.

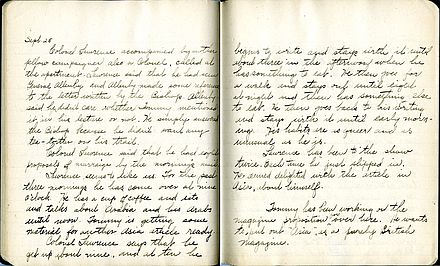

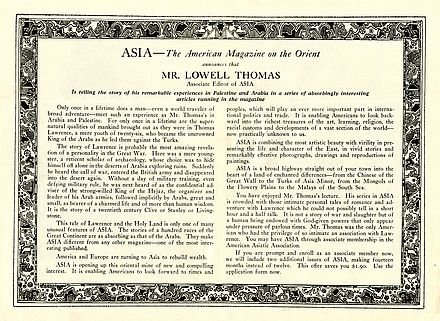

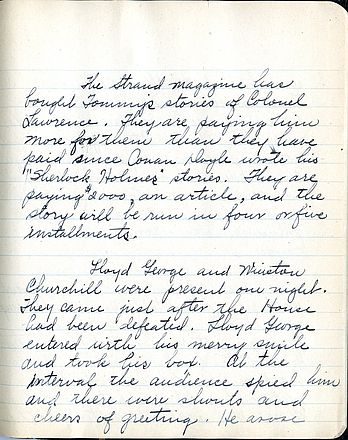

On September 25, she wrote her mother: “For the past three mornings in a row he has come over at nine o’clock. He has coffee and talks about Arabia and his Arabs until noon. Tommy is getting some material together for another Asia article ready. Lawrence has been to the show twice. Each time he just slipped in. He seems delighted with the article in Asia about himself.”

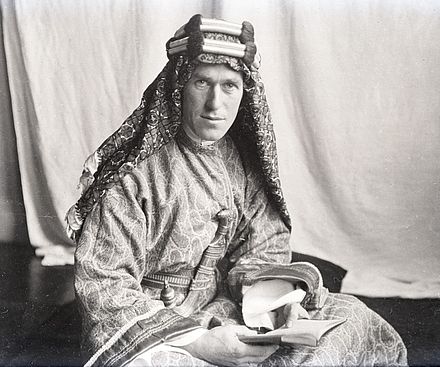

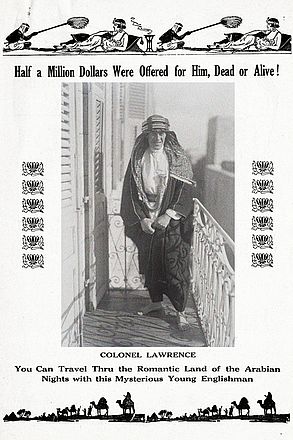

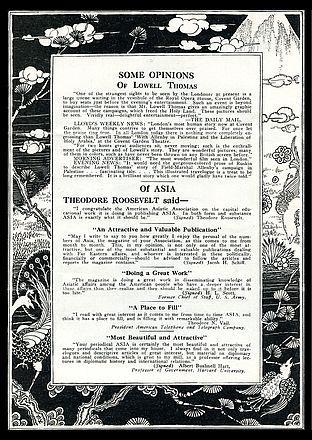

Also during the time of Lawrence’s visits, Thomas was writing articles for the American magazine Asia and the British Strand Magazine. And he was working on his book With Lawrence in Arabia, which would be published three years later in 1924. The informal visits to the Thomas’ home suggest that Lawrence was actually working with Thomas on his own portrayal in the Show and magazine articles. Lawrence even posed in the Thomas’ garden in Arab regalia for a series of additional photographs. These photos, again taken by Harry Chase, have become some of the most widely circulated pictures of Lawrence. Hand colored as lantern slides, these images were added to the Show and helped to create the Legend of “Lawrence of Arabia.” But in the uncropped versions available at Marist College, one sees the London apartment and the ivy-covered garden wall beyond the backdrops, as well as suits and shined street shoes on both Lawrence and Thomas beneath their Arab robes.

The only public acknowledgement by Thomas of these photo sessions came in 1935 after Lawrence’s death. Lowell Thomas wrote the English film producer Alexander Korda expressing the simple truth of the matter: “Lawrence worked with me in assembling material for a book and posed for further pictures for me. Everything I did was with Lawrence’s permission, and with his assistance. But he probably scoffed at it when talking to others because he always gave the impression of being a modest man. And he was modest in a complex way.”

Prior to Thomas’ show, T.E. Lawrence was virtually unknown outside a small British military and Near Eastern circle. The Show transformed him into one of the great heroes of the war. Thomas would quip that Lawrence “had a genius for backing into the limelight.”

Audio

Clip 12

Lowell Thomas on Lawrence’s interest in being in the spotlight.

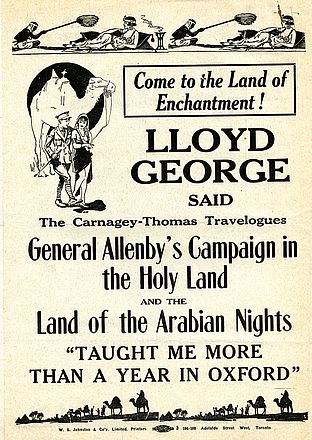

In an unprecedented move, the opening of London’s fall opera season was delayed so the show could continue at Covent Gardens. Every performance sold out, and in a swirl of success, Lowell and Fran Thomas were wined and dined by the English elite. But the pace was brutal and after nearly three months Lowell Thomas suffered physical collapse. Doctors told him, if he was to continue, he needed real rest between shows. Thomas and his wife moved out of town to the quiet of Wimbledon Common. Lawrence continued to visit them regularly walking the 24 miles out and back from his London lodging.

By mid-October the show moved to the huge Albert Hall where Thomas performed to 10,000 people a day. All the Lords and Ladies, Queen Mary, Prime Minister Lloyd George and Winston Churchill attended, and came back to see the performance. More than a million people attended the London show and it was shown to millions more on Thomas’ tour of the English-speaking world. Lawrence became a household name and the first superstar created by audiovisual media.

Certainly Thomas, with the likely assent of Lawrence, significantly embellished and romanticized the account. “And I believe,” Thomas proclaimed in a surviving script, “that this young man, who built the Arabian Army and liberated Holy Arabia, will go down in history alongside Francis Drake, ‘Chinese’ Gordon and Kitchener of Khartoum.” Surely, this ranks among the more impressive examples of hero-making in modern history.

Audio

Clip 13

Lowell Thomas on a white tie affair and success in London.